Transcript extra: Divestment

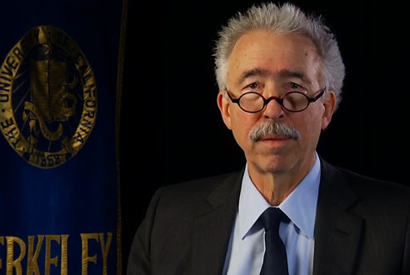

Transcript of a video conversation with incoming UC Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks, on the subject of divestment.

November 27, 2012

Transcript of an excerpt of a video conversation between UC Berkeley’s next chancellor, Nicholas Dirks, and Dan Mogulof of Berkeley’s Office of Public Affairs:

DAN MOGULOF: Floating around on the Internet is a claim that at some point in your past, you know, you signed a petition calling for Columbia to divest in all things Israel. And there is a lot of information surrounding that, or misinformation surrounding that, and I want to give you an opportunity to let us know exactly what happened there, what your role was and what your sort of philosophy is about sort of divestment type efforts insofar as the Middle East, or any other place in the world is concerned.

NICHOLAS DIRKS: Right. Well, when that particular petition was being circulated, I was chair of the department of anthropology and in fact, at some point, saw my name on a list and asked it to be removed. Truth is, I do not support divestment as a strategy for the university. I don’t support divestment with respect to Israel.

At the same time, many of my colleagues felt very strongly about this and many of them signed a petition, and it circulated widely at the time, which was 2002. There were, after that, all sorts of other controversies that developed about the climate for Jewish students on Columbia’s campus, about the nature of instruction and the department of Middle East studies, and indeed about the atmosphere at Columbia more generally, in which it seemed very difficult for some students to find safe spaces in which to talk about Israel where they didn’t feel that the basic context in which they found themselves wasn’t hugely not just anti-Israel, but by implication, anti-Jewish, and anti-Semitic. The first thing that we needed to do, of course, was to ensure that no one was made personally uncomfortable on the basis of their religion, as I said, their ethnicity, their entity. We, in fact, and it was my responsibility as the executive vice president for the arts and sciences, convened an unprecedented faculty committee to look into some of the allegations that had been made.

We took advice from Floyd Abrams, the great First Amendment lawyer. And we asked a professional in Columbia, Ira Katznelson, to chair a committee. And we made public the report that they came up with after their inquiry. We’d never done this before, but we did it this time, and did it despite the concerns on the part of many faculty that this might, in fact, have a chilling effect on public discourse in the university, from different perspectives, because we felt that we needed to make very clear that we were committed to a classroom environment in which students felt that they could think anything they wanted to think about political issues that might come up in their instruction.

At the same time, you know, you can imagine the kinds of passions that were unfurled around these issues more generally. And all kinds of allegations were made. In my case, I’m afraid some of these allegations are not true and some of them are ones that I find deeply troubling to me personally, but I was not a supporter of the divestment petition.

And I have even come out more strongly against any of the kinds of proposals for boycotts against universities. This speaks to not just the importance of the relationships that we’ve had at Columbia with Israel as a place, but also with Israel as a place where there are universities with whom we have very active exchanges.

And I think over the last few years, as we’ve had more exchanges and more open discussions, many of the constituents on campus, in fact, have found Columbia to be a less potentially threatening place, and indeed, a place that has been deeply supportive to all communities. You know, one of the things that has been so rewarding about my time at Columbia has been to be part of an institution that was more open and welcoming to Jewish students than was the case for other Ivy League institutions during many years in the 20th century. And most recently, through our deep commitment to access and diversity, we now have more students of color than any other institution in the Ivy League. And we have more under-represented minorities.

Now what this means, of course, is that we have students from all kinds of backgrounds for whom we have to be deeply concerned about their experience on campus. We’ve had students who have been concerned, for example, about the fact that as Muslims they haven’t had open access to prayer rooms for the kind of regular daily prayer that is part of their religious observance.

And we’ve had other issues as well for other students. And we’ve been always vigilant to ensure that the climate for all students, especially for students for whom coming to college as they do now often the first member of their family to come to college, means coming to a fairly strange and certainly culturally unfamiliar environment.

So the question of respect that you asked me about before is a question that has to run deep in terms of our relationships with students from all backgrounds. And we have to be attentive, also, to the larger context within which the kinds of things that students experience sometimes get magnified on a college campus, where there are pressures, obviously, on some communities more than on others, and some groups more than others. So we’ve worked very hard to be as open as we could possibly be and as responsive as we could be to the kinds of concerns that we hear. And, of course, we do hear them on a regular basis.

DM: So before we move on, I want to drag you back to the divestment issue, if you will. There are also reports that at one time your wife signed a petition, a divestment petition calling on Columbia to divest in all things Israel. Do you think that’s an appropriate issue? Is that something that people should be concerned about, what your wife may or may not have done in the past?

ND: Well, first of all, let me say that my wife is a ferociously independent person. She has many views, some of which I share and some of which I don’t. We have a long history of being able to talk about things and have different perspectives and even different views. That being said, she did, back in 2002, sign one of the divestment petitions that was circulating around Columbia, before she had either thought very much about the issue or for that matter really had any sense at all of what putting her signature to that document might mean. And she has subsequently thought a great deal about this issue, and she has regretted signing this. She has changed her position completely on issues of divestment. And indeed, I think she feels that it was an unfortunate and ill-thought moment in her own life and participation in things at Columbia.

That being said, I need to emphasize again that she has her views. They are not germane to the kinds of things that I believe that are part of being the next chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley. And I hope that she’ll be given the independence and the respect necessary for her to have her role on the faculty, as a member of the community and indeed as my partner as I move to Berkeley.